Backstory: Green Gables Opens Up Every Aspect of its Design/Build Process to Clients

Hand-holding is not something most builders want to do when it comes to clients, but Karl Rapfogel, president of Green Gables Design and Restoration, in Portland, Ore., freely admits it’s something he likes. In fact, he says, “We don’t mind holding hands; we prefer it. You never want to get to the next phase and realize somebody’s not happy.”

Green Gables makes at least 20 clients happy simultaneously through its large-scale remodels, smaller gut remodels, custom-built new homes, and some commercial work. And does so with a 50- person staff that includes an eight-member design team (five of whom are licensed architects) and no marketing—not even a job sign.

BUILD THEIR HOME

Founded by Rapfogel’s father-in-law, Lindley Morton, in 1977, Green Gables has a deep bench of current and former clients, and the company is now at the point where it’s remodeling, designing, and building the homes of former clients’ children. “We maintain relationships over generations,” Rapfogel says. That’s one of the main reasons why, he adds, the company doesn’t have to advertise; it’s all word-of-mouth. “No advertising has worked for us. [And that’s] part of our image.”

Located on the Pacific Ocean, this contemporary Oregon beach house designed by BORA Architects, in Portland, Ore., was built by Green Gables and is emblematic of the design/build company’s work.

Contrary to what marketing professionals may counsel, this strategy even sustained the company during the most recent recession. “We didn’t have to lay anyone off,” says Rapfogel, who admits it was a tough time, during which there was some attrition and Green Gables took on some commercial work to keep people busy. “But, still, we never threw up a sign,” he says.

Clients are referred by previous clients, family members, and architects (35 percent of projects are designed by outside architects). “Or, if someone has seen or heard about a house we’ve done, they reach out to us,” says Rapfogel, who believes this pre-vets clients.

If it’s a design/build project, Green Gables meets with prospects to determine their goals. “We establish their hopes and dreams,” Rapfogel says. “We spend a lot of time in the schematic phase of designs to get clients’ needs on paper.” Once Green Gables has a good sense of a client’s aesthetic, the company determines which architect would be the best fit. “We, as a company, don’t have a specific aesthetic,” he says. “We’re extremely client-oriented and have done everything from very modern and contemporary projects to completely traditional homes. We want to find out who people are and build their house.”

Most of the people who come to the firm, Rapfogel says, “have specific ideas about what they want, are detail-oriented, don’t want to cut corners, and want transparency. They’re business-savvy people, and we cater to them.”

PORTLAND-BOUND

Originally from St. Louis, Rapfogel studied art and design, graduating in 2003 from New York University, where he met his wife. He worked as a sculptor and printmaker, but after a few years, he says, New York was too expensive and too fast paced and the couple didn’t like the culture. So they moved to Portland, Ore., in 2007, where Rapfogel began working for his father-in-law as a laborer.

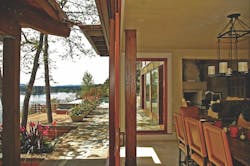

Designed and built by Green Gables, this Lake Oswego home was a foundation-up rebuild that features large sliding doors, specialty plaster, abundant outdoor living space, and a new boathouse.

“I wanted to get in on the ground floor and meet my co-workers,” Rapfogel says. “That’s the company culture anyway. Everyone is expected to do whatever we have to do. I started out digging holes, hauling lumber, and keeping jobsites clean.”

After two years, he began assisting carpenters and then managing projects. Five years later, he helped Morton revamp office systems and update processes. He purchased the company soon after with Narada Fairbank, a Green Gables project manager who had also started at the bottom. “He’s more the field guy and I’m more the business guy,” Rapfogel says. “We make a good team.”

WORK TOGETHER

That team aspect characterizes the company from the top down and filters through to its client relationships. “Everything we do is completely open-book, even the bidding process,” Rapfogel says. Unless clients say they don’t want that level of involvement, Green Gables shares “every cost on the invoice from subcontractors to suppliers to the dumpster and porta-potty,” he says.

Clients see the hard costs and the company’s fee and markup on a detailed spreadsheet. They see any change orders (of which there are usually only a few, according to Rapfogel) carefully documented.

Green Gables works on time and materials, with a guaranteed maximum. “We’re all working together and aren’t hiding anything. If we come in under the guaranteed maximum price, we don’t ask for the maximum. Clients get the best of both worlds.” Their only cushion is a contingency, which varies by project. “We’re good at estimating,” Rapfogel adds.

For each project, Green Gables has a site-specific project manager who works on just one project at a time, unless it’s a very small project. Rapfogel tells clients up front that there’s “a bit of a premium to be paid for that, but we don’t like the PM bouncing around.”

The company subcontracts its electrical and plumbing work, and carpentry is done in-house by 38 carpenters and laborers. Green Gables also does its own window and door installation. “Those are a big liability in the Pacific Northwest, with the amount of wind we get,” Rapfogel says. “The weakness in the façade is in the fenestration. We prefer to do that in-house and not sub it out.”

While the company uses sustainable building practices, Rapfogel says that because the firm is so client-focused, Green Gables doesn’t push an agenda. “We see ourselves as problem-solvers. We’ll try anything and study anything, but we don’t come in with a set agenda.”

Rapfogel says he can see himself doing this work forever, although he admits the attention to detail can be demanding and stressful. “It’s not for the faint of heart, but the reward is when you see the client moving their furniture into the house. It’s a good feeling.”

Stacey Freeed covers design and the built world from her home in New York state.

This story originally ran in the Winter 2019 issue of Custom Builder. See the print version here.