Custom Remodel: A Childhood Log Cabin Grows Up

As the saying goes, they don’t make ’em like they used to. This certainly applies to the projects we feature this month. Crafted from such materials as stone, brick, and Canadian cedar logs, these homes all contain elements worth preserving, but each was in need of significant intervention.

Renovating an entire house with the intent of maintaining its character while providing for modern living requires finesse and is sometimes more expensive than just starting over. But, more often than not, the benefits far outweigh the effort. “The cost to do a gut renovation is often the same as tearing down and building new,” says Gloria Apostolou, principal of Toronto-based Post Architecture, “but you can’t build back a heritage home, so an extensive renovation is more appropriate in some cases.”

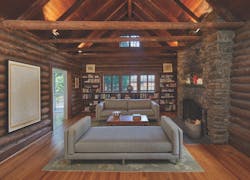

The story-and-a-half great room highlights the home’s log cabin origins and was mostly left as-is.

Image: Anice Hoachlander/Studio HDP

John DeForest, principal at DeForest Architects, a residential architecture firm in Seattle, shares a similar perspective. “Keeping the bones of a house, along with the details, has huge value,” he says. “Take into consideration the client’s emotional connection, plus the home’s potential resale value, simpler permitting, and inherent sustainability.”

Once a client decides to renovate rather than tear down, selecting the right contractor can make or break a project, DeForest says. A high level of craftsmanship and good organizational skills make a big difference in pulling off such complex undertakings. “Smooth project management is going to save me and the client stress,” he explains, “and that’s a lot of added value.”

A Childhood Home Grows Up

Originally built in 1919 as a log cabin guest house, this home has had just three owners. As it happens, the third and current owner also grew up in the house. Her renovation goals involved making the 101-year-old home livable, while maintaining its character.

Logs from an opening cut into the wall facing the new kitchen were repurposed and crafted into a 12-foot-long dining table (see photo below) for the client, who frequently hosts dinner parties.

Image: Anice Hoachlander/Studio HDP

Prior structural changes, and the client’s budget limits, made achieving the desired updates a challenge. Fortunately, the owner found David Haresign, of Bonstra | Haresign Architects, in Washington, D.C., who embraced the project. “The client wanted something modern, family-friendly, and sustainable—she’s very conscious of sustainability—with better sleeping and bathing spaces. She also entertains frequently and hosts fundraisers,” Haresign says. “But the house was a chopped-up mess.”

This was a significant project for Bonstra | Haresign Architects, which generally accepts only a few single-family projects.

Image: Anice Hoachlander/Studio HDP

During the 1980s, the client’s mother had commissioned an addition to the home that made the house complicated: users had to step up and then back down on the main floor; a dormer added on the second floor looked disproportionately large; and cuts in the logs corrupted the building’s structural integrity.

Haresign credits the structural engineer and the skill of the contractor’s framer with making it possible to incorporate the “unkind” addition because tearing it down would have blown the client’s budget.

“The second floor was about to fall into the first floor, which we didn’t realize until midway through construction,” Haresign explains. “We brought in a structural engineer experienced in working with historic buildings, reframed the floor around the addition, and added roof ties.”

Image: Anice Hoachlander/Studio HDP

The contingency fund Haresign always includes (7% to 10% for complicated projects) absorbed the added expense of around $10,000. The investment also allowed for widening openings and strengthening the connection between the home’s core and the addition. Anice Hoachlander/Studio HDP

Image: Anice Hoachlander/Studio HDP

With structural issues resolved, the team expanded the existing addition, adding a kitchen/dining area on the main floor and a master suite above. The team also combined the cabin’s jumble of tiny rooms to create a modern space that accommodates up to 50 people.

Image: Anice Hoachlander/Studio HDP

Getting natural light into this interior living room led to some innovative design strategies, too. “We moved the vertical organization from the addition to the central cube,” Haresign says. “A simple stacked stair with ridge skylights directly above it and adjacent glass flooring on each level allow light to flow all the way down to the basement.”

The story-and-a-half great room is the only area where original cedar logs remain exposed. For other log walls, the team removed the plaster and replaced it with insulation and drywall. To bolster its sustainable bona fides, the house now features insulated walls, high-efficiency fixtures and appliances, and a geothermal system to help meet the client’s sustainability goals.

Photo: Anice Hoachlander/Studio HDP

And, adding to the environmentally friendly story, the client also donated old cabinets, doors, fixtures, and appliances; had the historical casement windows rebuilt with insulated glass; installed a permeable parking court; and landscaped using native plants.

“The renovation made the house 50% bigger and the client uses less energy,” Haresign says. “One of the most sustainable aspects is reimagining an existing home and extending its use for generations.”

Project: Somerset Cabin, Somerset, Md.

Architect, interior design, kitchen design: Bonstra | Haresign Architects, Washington, D.C.—David Haresign, FAIA, architect/designer, and Adam Greene, AIA, project architect/designer

Builder: Thorsen Construction, Alexandria, Va.

Structural engineer: Keast & Hood, Silver Spring, Md.

Landscape design: Jennifer Horn Landscape Architecture, Arlington, Va.