Resilient Design: Ready for Natural Disasters

The onslaught of hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, mudslides, wildfires, and earthquakes that has plagued the U.S. in the last several years has given rise to a new concept: resilient design. More than just a buzzword, resilient design is about protecting inhabitants, ensuring that key systems will continue to operate during and after a disaster, and on a macro level, creating a home that lasts 100 years or more.

More Stories About Building on Challenging Sites:

* Laying the Groundwork

*Triumph over Tough Sites

* Tearing Down and Building Anew

* Building Custom on a Remote Site

New technologies, such as battery backup systems, are impressive and easy ideas for customers to latch onto, but builders that practice sustainable design and construction are already armed with the necessary tools to create resilient homes. And while clients may not be familiar with the term “resilient,” they understand what it means to have a house that will remain standing, despite almost anything nature throws at it.

This Martha's Vineyard, Mass., home occupies a wooded bluff. The design employs passive ventilation and ample daylighting. The fireplace offers a backup location for cooking if needed. Pictured is Abbie Rogers of South Mountain Co., the builder/designer. Photo: Bob Gothard

“I’ve been promoting the concept of passive survivability—that we should be designing and building houses that will maintain habitable conditions if they lose power,” says Alex Wilson, president of the nonprofit Resilient Design Institute, in Brattleboro, Vt. “To do that, you need to incorporate a very robust building envelope: well insulated with high-quality, high-performance windows and durable construction. It’s also about incorporating passive solar heating and cooling and natural ventilation.”

Nathan Kipnis, founder and principal of Kipnis Architecture + Planning, in Evanston, Ill., recently started a division called NextHaus Alliance that will design nothing but ultra-high-end resilient homes. NextHaus is a team of professionals with expertise in architecture, construction, interior design, landscaping, and technology that works with clients to minimize complexity and maximize budgets.

“Resilient design is focused on changing weather patterns, so the response in each geographic region will be different,” Kipnis says. “For example, here in the Midwest we’re seeing rains that are increasing in frequency and intensity, with associated higher winds.” To address these issues, Kipnis installs a continuous ice and water shield under the entire roof, not just at the bottom 2 feet of the perimeter, to keep it watertight, especially if the roofing is blown off. He’s also working on whole-house battery backup systems that are connected to solar panels and set up in a separate subpanel that controls key systems that need backing up during power outages. “These typically include refrigerators, sump pumps, garage doors, ceiling fans, and a few power outlets,” Kipnis says.

Clients will likely begin prioritizing, he says. Instead of a home theater or upgraded kitchen cabinets, for example, they’ll put in rooftop solar, which is becoming less expensive. Some of the push toward resilience is due to recent catastrophic events. After Superstorm Sandy ravaged the East Coast in 2012, FEMA revised its flood-zone maps; new homes must now be at least 8 feet above flood elevation. “But many towns are asking for 10, 11, 12, and 13 feet,” says Richard Bubnowski, owner of Richard Bubnowski Design, in Point Pleasant, N.J. “They don’t want ductwork or any part of the structure dipping down into that base flood elevation. So an awful lot of what we do is based on building codes, whether they’re state, local, or FEMA, but it’s always better to exceed code.” Above code or not, there’s sufficient demand from clients—especially those who have lived through a natural disaster—to justify kicking things up a notch.

For a home on Martha's Vineyard designed and built by South Mountain Co., the electrical system’s battery bank and inverters were installed in the basement of a custom-built barn. Photo: Derrill Bazzy

High Winds and Bitter Cold

South Mountain Co., a design/build firm in West Tisbury, Mass., uses site-built wood moment frames to keep houses from racking in the high winds that can buffet Martha’s Vineyard. A custom-built steel moment frame isn’t always necessary, notes South Mountain’s Matt Coffey, project architect and owner. Coffey says there are some clever ways to tie the moment frame back to the foundation and still .

South Mountain Co. starts with a baseline of super-insulated houses, which hold snow on the roof much longer than poorly insulated houses. “A common snow-related issue with roof water intrusion is the result of ice damming,” Coffey says. “This happens when a poorly insulated roof melts the snow quickly and the water gets to the eaves. In super-insulated homes, the melting is slower and is consistent across the surface of the roof and eaves, avoiding ice buildup. “During a power outage, the pipes won’t freeze—barring broken windows or other structural damage—and there’s a lag in heat loss so that the interior stays comfortable for longer.”

South Mountain Co. designed the one-story home to have a sunken garden and admit daylight to the lower level. Photo: Bob Gothard

Clients who want their homes to be fully habitable and operational during a power outage have a range of options, Coffey says. “We use only electrically driven systems and equipment that can be paired with solar photovoltaics and a battery system, or a small backup fossil-fuel generator,” he says.

While the battery backup costs about $50,000, Coffey says it’s a tremendous energy saver and a good solution for remote sites where it would be prohibitively expensive to run utility lines. He envisions that battery technology will become increasingly affordable: “In the next 10 years or less, it could replace fossil-fuel backup generators.”

Designing for Wind, Lightning, and Rain

The home in Tampa, Fla., was completed in summer 2017, just before Hurricane Irma made landfall. When it was time to evacuate in anticipation of a storm surge from Tampa Bay, the clients elected to ride it out inside their new home, built to withstand 130 mph winds.

“During the storm, they never lost power and could barely hear the 100-plus mile per hour winds outside, due to the impact windows we used,” says Gary Brown, co-owner of Tampa-based Sterling Bay Homes. “The house sustained no damage during the storm.”

This Tampa, Fla., home survived Hurricane Irma without loss of power and sustained no damage. Sterling Bay Homes adheres to strict FEMA flood-elevation regulations and installs flood vents in garages and garage doors and breakaway ground-floor walls in hurricane zones. Photo: Shannon Corr Photography

Resilient construction in the Tampa area has more to do with the shell of the home and design of the exterior fenestration, Brown says. Houses are raised to minimum FEMA flood elevations, with flood vents in garages and garage doors, and breakaway ground-floor walls in hurricane zones. Added costs are to be expected. Raising homes up from a FEMA floodplain can double or triple foundation costs. Walls made of concrete block and concrete always perform better than wood when it comes to water intrusion, but they can add 20 to 30 percent to the cost of the building shell, he notes.

Gas-powered home generators have become the norm in the Tampa area, which Brown calls the lightning capital of the U.S. “Lightning-strike power surges are more of a problem than the occasional 10-to-15-year hurricane that might knock the power out for a day or more,” he says.

For safety and stability during earthquakes, this Los Angeles home by Landry Design Group is anchored to bedrock on a steep site and exterior walls are stacked against the hillside and the house above. Photo: Erhard Pfeiffer

Surviving Earthquakes and Mudslides

Homes perched on the hillsides of Los Angeles are susceptible to a variety of natural disasters, particularly earthquakes and mudslides.

“We design first of all for earthquakes,” says William Mungall, an associate with Landry Design Group, in Los Angeles. “We work with structural and civil engineers on the side walls and foundations, discussing the options and how they can be built above code.” On a site resting mostly on bedrock, caissons are buried down to the bedrock. “It’s about as stable as you can get,” Mungall says.

If there is considerable fill on a site due to a previous landslide or subdivision grading, Landry and the engineers recommend a mat-slab foundation, which evenly distributes the weight of the house over the entire foundation rather than around the perimeter. Mat-slab foundations exceed what builders in the area typically do, he says. “If there’s some movement in the house, the whole thing shifts a bit and you won’t notice it,” says Mungall. “You end up with a lot less cracking and settling.”

To protect new homes from severe flooding, Houston’s Frankel Building Group utilizes a pier-and-beam foundation that lets water flow underneath the house. The covered veranda of this home is raised a few steps above the pool area to minimize the possibility of water reaching the interior. Photo: Courtesy Frankel Building Group

Flooding: Houston’s ‘Flavor of the Day’

Lately Houston has received more than its fair share of hurricanes, wind, and rain, but the “flavor of the day,” according to local builder Kevin Frankel, is flooding. Homes built with Frankel’s pier-and-beam foundation system escaped major damage during the floods on tax day and Memorial Day 2017, as well as the impact of Hurricane Harvey.

Pier-and-beam construction can cost clients an additional $10,000 to more than $50,000, depending on home size and whether the master bedroom is upstairs or down. But it’s the only option for those building in a 100-year floodplain because it raises the finished first floor above flood level. Outdoor living areas are a few steps below the first floor, so water is less likely to flood the interior. In pier-and-beam homes, Frankel uses open-cell spray foam insulation everywhere but in the floor system to allow vapor transfer to the outside. “I call it resilient because it creates sustainability in the home,” he says. “You won’t get cracked or rotting windows.”

Next Steps to Resilience

Once green and sustainable measures are implemented and codes met, builders and architects can go further with renewable energy systems—typically solar panels and battery storage systems. Wilson, of the Resilient Design Institute, lives in a net zero energy home with a solar system that feeds power to and draws power from the grid. In the event of a power outage, a new type of inverter executes a hard disconnect from the grid, allowing the home to continue drawing power from rooftop solar. “It’s a pretty simple, affordable way to maintain access to electricity during an extended outage,” he says, as opposed to more comprehensive (but more expensive) electrical storage through a battery system.

Whether you’re building to code or going above and beyond, the goal should always be to design and build a house that will last for generations. Says Cary, N.C., builder Evan Bost, “Beautiful design is another key piece of resiliency. When you build something, you want it to be there forever, as opposed to it being an eyesore 20 years down the road.”

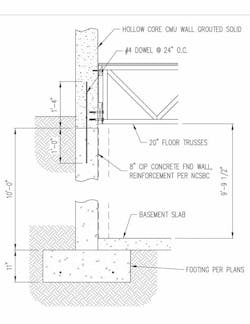

Bost Custom Homes, in Cary, N.C., offers masonry framing as a more durable, fire-resistant option. Illustration: courtesy Bost Custom Homes

When Masonry Makes Sense

In 1999, Bost Custom Homes was the first builder in the Cary, N.C., market to start offering masonry framing as an option. Masonry framing is an upgrade from traditional stick framing that isn’t susceptible to fire or water damage, says Evan Bost, director of marketing and building performance.

“It’s a little more complex from a planning and structural-engineering standpoint because all of the load points are transferred into the masonry,” Bost says. “The 8-inch block wall actually serves as the load-bearing point for the roofline and a lot of the major floor and wall systems. For the most part, we’re tying the floors and roofs directly into that masonry wall.”

Masonry block is built up around a bare-bones wood frame. The concrete walls are hollow concrete block filled with rebar, concrete, and foam. (See illustration, above.) Masonry framing costs approximately 3 to 5 percent more than stick framing, but offers multiple benefits including energy efficiency, fire resistance, pest resistance, and sound dampening, Bost says. “Obviously, the internal parts are flammable, but in a masonry-framed home, the structure itself isn’t going to collapse in a fire,” he says.

FEMA-certified safe rooms—certified to survive a tornado rated EF5 (EF2 or higher is considered a significant tornado)—are easy to create in a masonry-framed house. “We try to tuck them in a basement, making them part of the wall slab,” says Bost. “So the ceiling and walls are concrete, rebar, and steel reinforced, and there’s a big steel door.”